I wrote last week about imaginary topographies in Anne of Green Gables and how cultivating imagination with respect to place can deepen your relationship with your natural surroundings. I’m now two books deep in the series, and one of the things that’s standing out to me is the phrase “cultivate your imagination,” which Anne uses repeatedly.

Even before embarking on my reread I’d been working on rekindling my own imagination, which feels like it’s atrophied to the point of a vestigial limb. Reading Anne has been great for that project, both because I have such vivid memories of reading it the first time that I can almost tap into the sense-memories of those imaginings, and because it’s a series that canonically deeply values the imagination.

From the moment Matthew Cuthbert picks her up from the train station, she keeps up a near-constant monologue of imaginings spurred by what she sees, the people around her, and her own circumstances and how they could be different. To Anne, imagining seems to be as necessary to her existence as breathing, and as natural. But that isn’t true of all of the characters—certainly not the rigidly pragmatic Marilla, and not even Anne’s “bosom friend” Diana, who is a bit more prosaic than Anne would prefer. Diana envies Anne’s imagination, complimenting her on a story she wrote:

“How perfectly lovely!” sighed Diana…“I don’t see how you can make up such thrilling things out of your own head, Anne. I wish my imagination was as good as yours.”

“It would be if you’d only cultivate it,” said Anne cheeringly.

Probably because of the botanical focus of my other reading this month, I’m struck by L. M. Montgomery’s use of the word “cultivate.” She could have said “train your imagination,” or “exercise your imagination,” or simply “use your imagination.” But instead, she chose the word “cultivate,” which evokes the relationship of love and care towards nature that echoes throughout the books.

It also implies that imagination isn’t just something you have or don’t, it’s something that can be tended. Some people might be more naturally imaginative than others, but everyone has the capacity to cultivate their imaginations. Maybe that means that imagination is less like a mythical Muirian “untouched wilderness1”, and more like a garden.

And so, I’m brought back to Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses (I said I couldn’t shut up about this book this month, didn’t I?). She writes that “Gardens have been defended as apolitical spaces—famously, at the end of Voltaire’s Candide, the title character retreats to ‘tend his garden,’ a decision that has often been framed as a withdrawal from the world and politics.” But Solnit argues that gardens aren’t apolitical at all. She writes that “A garden is what you want (and can manage and afford) and what you want is who you are, and who you are is always a political and cultural question.”

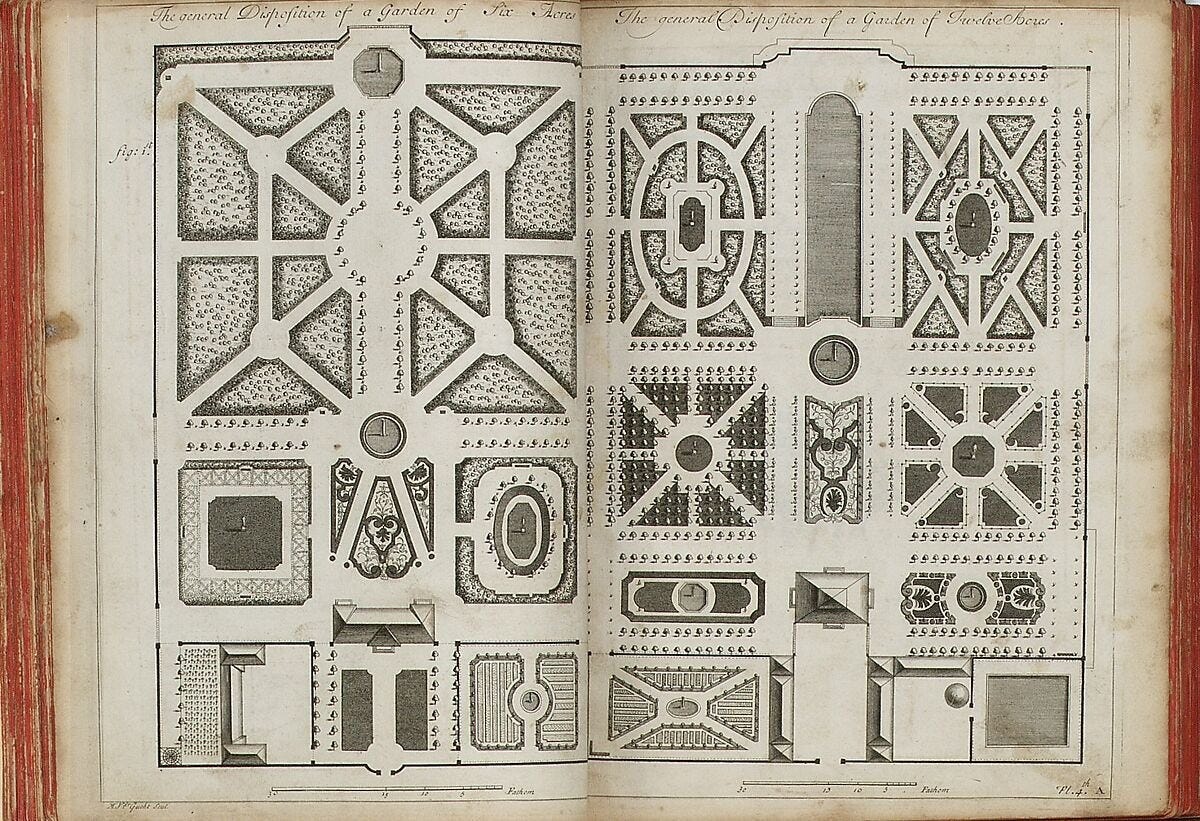

For example, she describes how the gardens of European aristocrats in Voltaire’s era tended towards nature-defying displays of “geometrical arrays and trees trimmed into cones and other formal shapes,” but in the latter half of the eighteenth century, they “took on an aesthetic of naturalness—often of a carefully landscaped, designed, and laboriously executed naturalness that celebrated the aesthetics of the natural world while presuming to groom and improve it.” This shift, she argues, was a subtle play to position the aristocracy—specifically, the English aristocracy and the social hierarchy it represented—as being “natural” itself, with “power and privilege…rooted in the actual landscape.” Their gardens reinforced a narrative that supported that social order even as the process of privatizing the commons uprooted many of the people who actually worked the land, forcing them into industrial labor in cities or to emigration. Thus, gardens not only reflect the politics of their time and place, but help to shape them.

Solnit writes that “...in Orwell’s time the natural world was often imagined as outside the social and the political.” This attitude persists to some extent even now, when the impacts of the social and political on the natural world—and vice versa—are becoming more and more inescapably apparent. I think imagination occupies a similar space—as something that’s often considered unnecessary, frivolous, escapist, and in those ways probably apolitical. But as with a garden, that’s a misapprehension.

As I usually do when scratching around a new post, I did a quick Google search on “cultivating your imagination,” hoping to encounter some odd Reddit thread or interesting Wikipedia article. It was a nasty shock when what came up instead was the AI summary, telling me that “To cultivate imagination, you can engage in various activities and practices that encourage creative thinking and open-mindedness.” There is nothing on this earth more deeply opposed to the practice of actually cultivating your imagination than AI telling you how to do it.

Much of the rest of what I found in my Google search was no more encouraging than the AI summary. Medium articles titled things like “3 Steps to Imagination” framed around the idea that imagination is valuable in many so-called “thought-work” fields, and will only become more so as the world becomes increasingly automated and AI-driven. They’re full of words like “generate,” “stimulate,” and “optimize,” and position imagination as a commodity.

What is imagination for? This question reminds me of the 2023 movie Woman of the Hour in which a young woman on a dating show asks the male competitors the question, “What are women for?” Of course, like women, imagination is not really “for” anything, it simply exists. So does nature. But the way we answer that question at any given time is a great indication of what our culture values. Is nature something to be vanquished and subjugated? Are women? Is imagination a commodity?

Imagination certainly does have a place in all areas of our lives: from leisure, to labor, to building relationships and community. That’s where the idea of imagination as a garden comes in—nature qua nature might not be “for” anything, but a garden is tended with intention, whether it’s a flower garden or a vegetable garden or a medicinal herb garden. Imagination can be cultivated with similar intention.

I’m reminded again of the idea of sleep and dreaming as “the last vestige of humanity that capitalism cannot appropriate,” as Jonathan Crary put it in his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. I’m tempted to say that imagination is similar, but clearly capitalism is doing its best to appropriate it and quash all parts of it that don’t serve its agenda. If you refuse to let your imagination be yoked in service to the empire, it can keep alive your capacity to imagine things other than what they are, which is the first step to making them other than what they are.

So whether you’re naturally full to the brim with imagination, like Anne, or a little more prosy, like Diana, we can all benefit from cultivating our imaginations. Think of your imagination like the garden in The Secret Garden: long overgrown and overlooked, but with care, attention and cultivation, ready to bloom again.

If your imagination were a garden, what would it look like? What kinds of plants would grow there? Would it grow in orderly rows, or would it ramble?

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2021-2-march-april/feature/john-muir-native-america