CN: Brief mention of suicidal ideation.

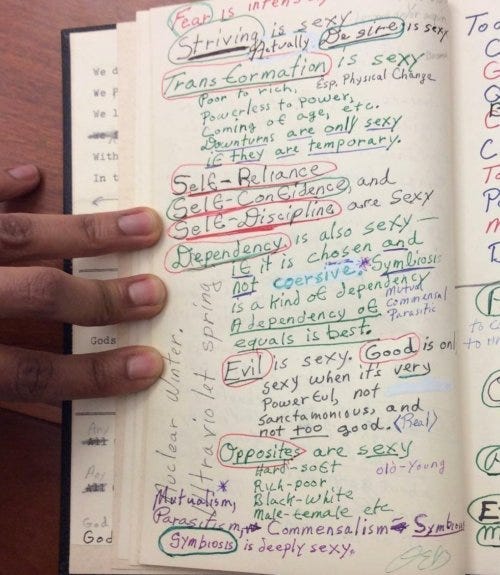

A picture keeps popping up in my Substack feed of Octavia Butler’s list of what’s ‘sexy.’ To Butler, striving is sexy, as are desire, transformation, self-reliance, self-confidence, self-discipline, dependency (if it’s mutual), evil (apparently always), good (only when it’s very powerful, not sanctimonious, and not too good), opposites, parasitism, commensalism, and symbiosis (deeply sexy).

Like most of Butler’s notes, this list stands out to me because it’s so idiosyncratic and feels deeply personal, like it was written just for her rather than with an audience in mind. These were probably dynamics she wanted to explore in her writing, but she doesn’t feel the need to give any explanation.

Most writers whose ‘processes’ are talked about—especially male writers—tend to be shrouded in a kind of intellectual mystique that obscures the practical, unsexy aspects of the writing life. Their notes read as though they were written for an audience, by a persona.

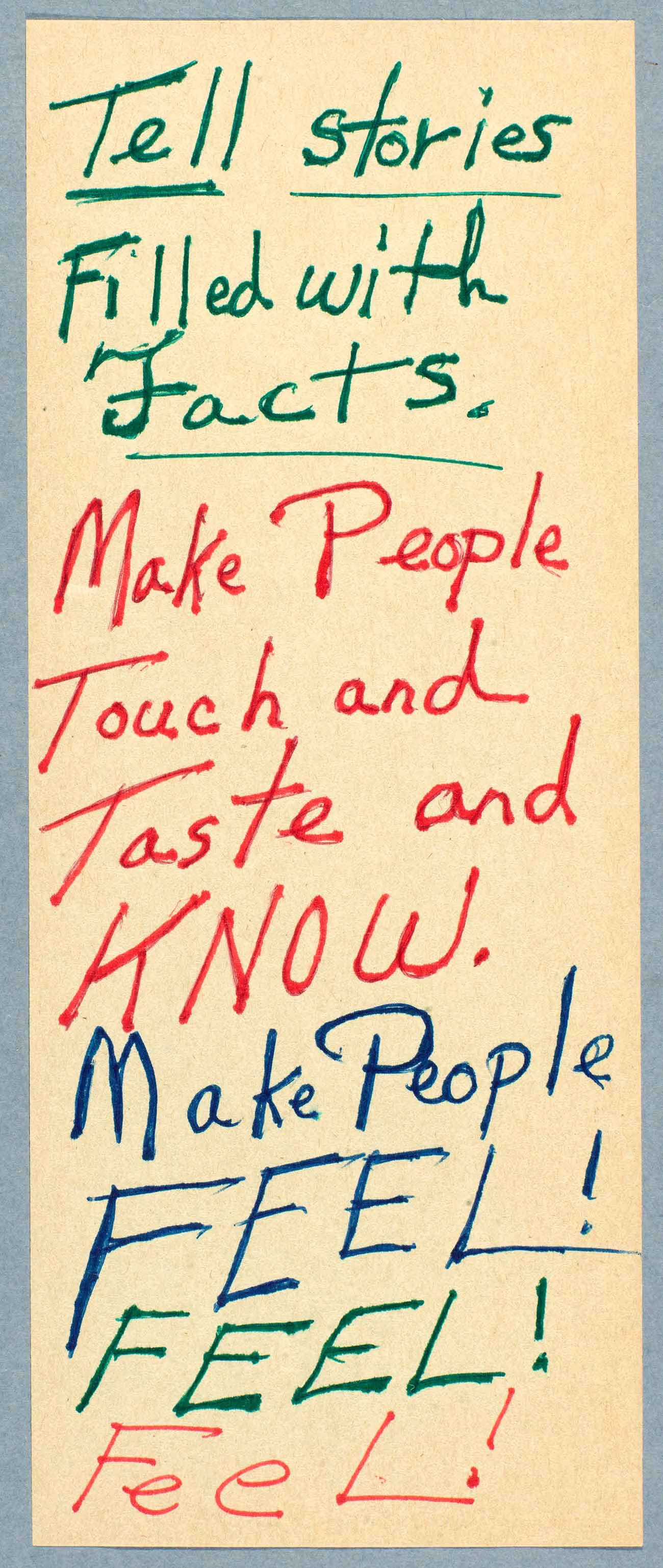

Butler’s notes are the opposite. Here is a woman who is clearly not beholden to things being ‘just so.’ She writes in blue, black, green, red, sharpie, and pencil. Her handwriting is inconsistent and messy. She writes side to side, up, down, smushed in the margins, diagonally. Her notes, like her writing, are so alive.

I don’t know if she wanted her notes to be published. I hope she did; I find them so comforting.

As a lonely kid, I used to make lists of the characters in books and movies and TV shows that I admired, and the qualities I admired in them. Then I would go through the lists and look for similarities to try and find out what sort of person I wanted to be based on what I found admirable in other (albeit mostly fictional) people. There were a few common threads. The characters I loved best were all odd, intelligent loners, most of whom worked thanklessly at things that nobody else considered valuable. I remember writing that they ‘didn’t care what people think,’ but looking back, I think they probably cared very much what people thought, and were hurt by being misunderstood, and doubted themselves every day. But somehow, they couldn’t let whatever it was go in order to be considered successful, or admirable, or correct. They were people who had secrets.

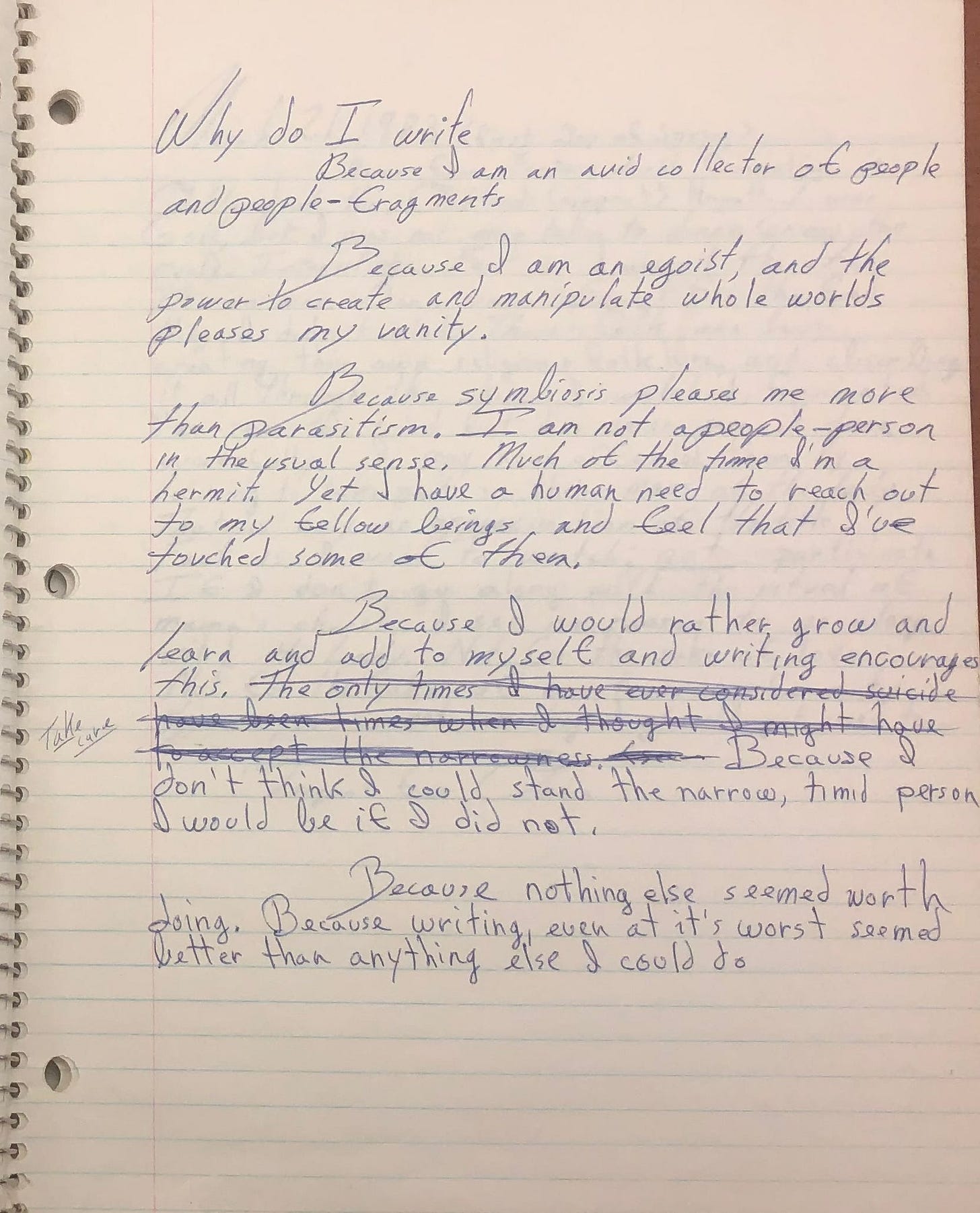

Looking at Butler’s notes, I think she must have been one of these people. In the note above, she wrote that “I am not a people-person in the usual sense. Much of the time I’m a hermit. Yet I have a human need to reach out to my fellow beings, and feel that I’ve touched some of them.” Odd, intelligent loner, check.

She crossed out an admission that the only times she considered suicide were when she thought she might have to “accept the narrowness,” presumably of a life without writing, stripped of imagination. She chose to be a writer because “nothing else seemed worth doing. Because writing, even at its worst seemed better than anything else I could do.”

Still, in the early years of her career, she received very little external support. In a 1994 conversation with Jelani Cobb, she said, “Do you know who encouraged me? …Nobody.” Without external validation, she had to rely on her own internal systems, discipline and self-trust.

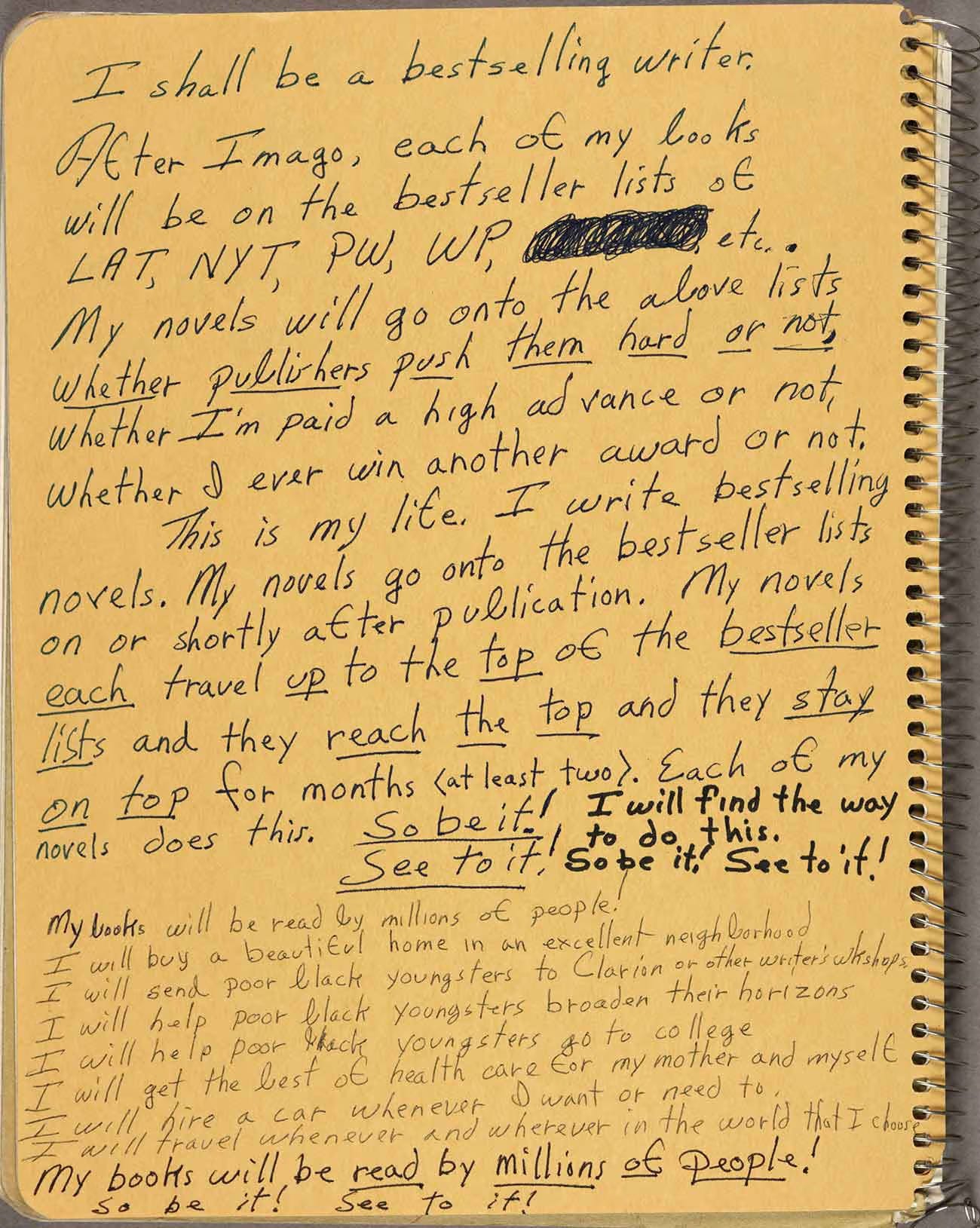

Her goals for external validation—both financial and creative—were honest, practical, and clearly-defined. This note, scribbled on the back of a 1988 notebook, details her goals for her writing, including specific bestseller lists she would make, that her books would reach the top of these lists and stay there for at least two months. The money she would make from her books would allow her to buy “a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood,” hire a car whenever she needed, get the best possible health care for herself and her mother, travel wherever and whenever she wanted, and help give Black kids access to opportunities like writers’ workshops and higher education. Though she won a MacArthur Fellowship and other prestigious literary awards, her books would not make the bestseller lists until after her death.

What I love about these notes is that they show she wasn’t stuck in some art-for-art’s-sake fantasy. She admitted to herself that selling books was a path towards financial self-determination, and living the kind of life she dreamed of and knew she deserved, sealed with her own ritual phrase: “So be it! See to it!”

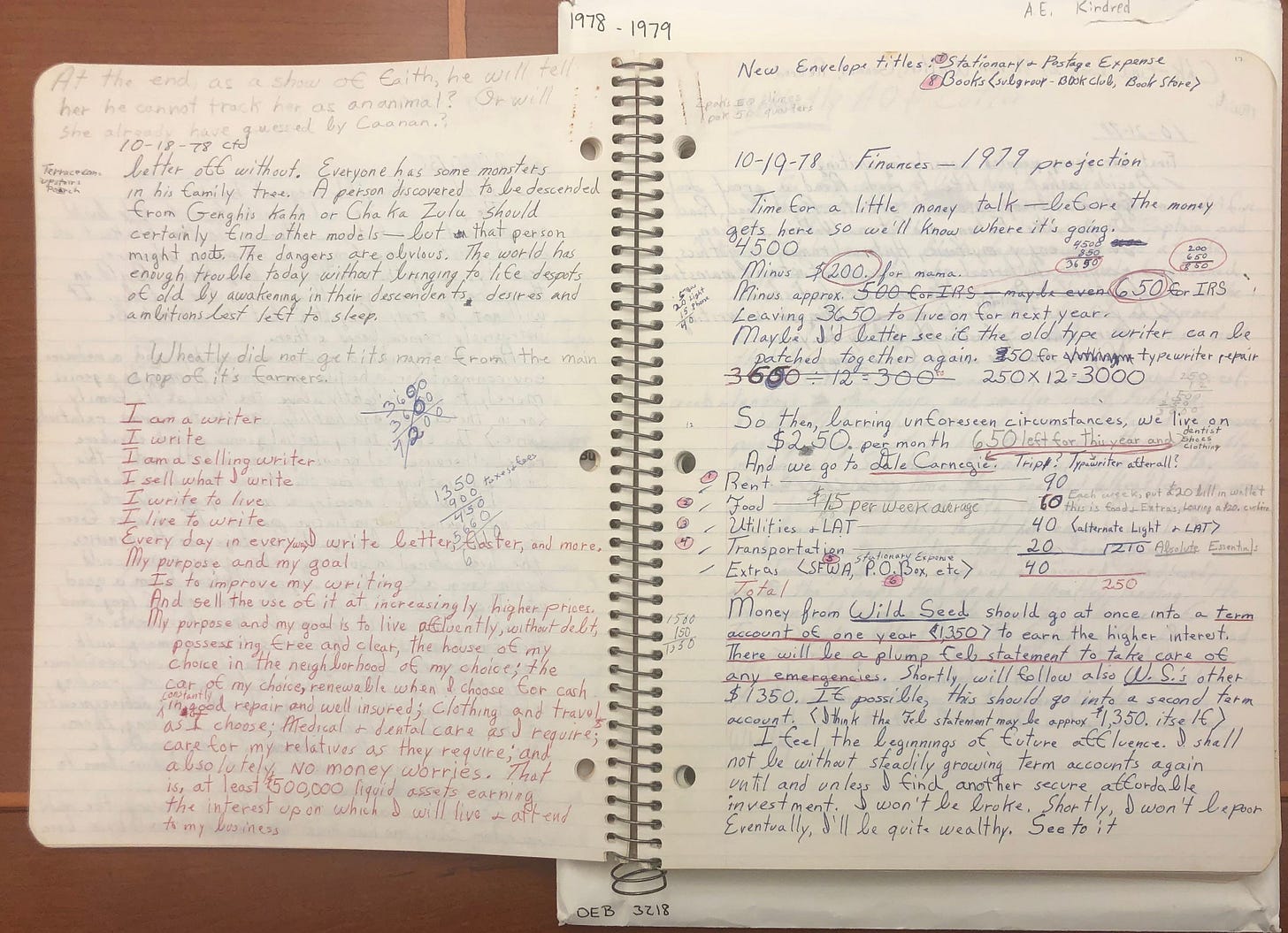

On one page of affirmations and financial calculations from 1978, Butler writes:

My purpose and my goal is to live affluently, without debt, possessing free and clear, the house of my choice in the neighborhood of my choice; the car of my choice, renewable when I choose for cash constantly in good repair and well insured; clothing and travel as I choose; medical + dental care as they require; care for my relatives as they require, and absolutely no money worries. That is, at least $500,000 liquid assets earning the interest upon which I will live + attend to my business.

Her definition of ‘affluence’ might seem modest (though in today’s world it’s a huge stretch for most of us) but it highlights what really makes a person rich: the freedom to choose. Self-sovereignty was her financial goal for her writing.

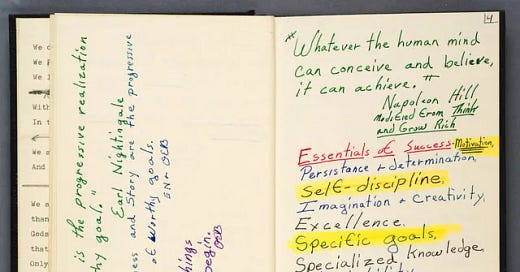

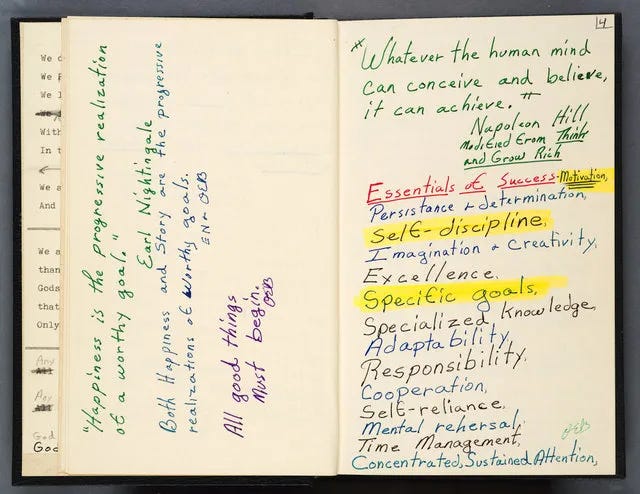

But while her external goals were clear, Butler’s self-defined “Essentials of Success” aren’t characterized by external impact, but by internal work.

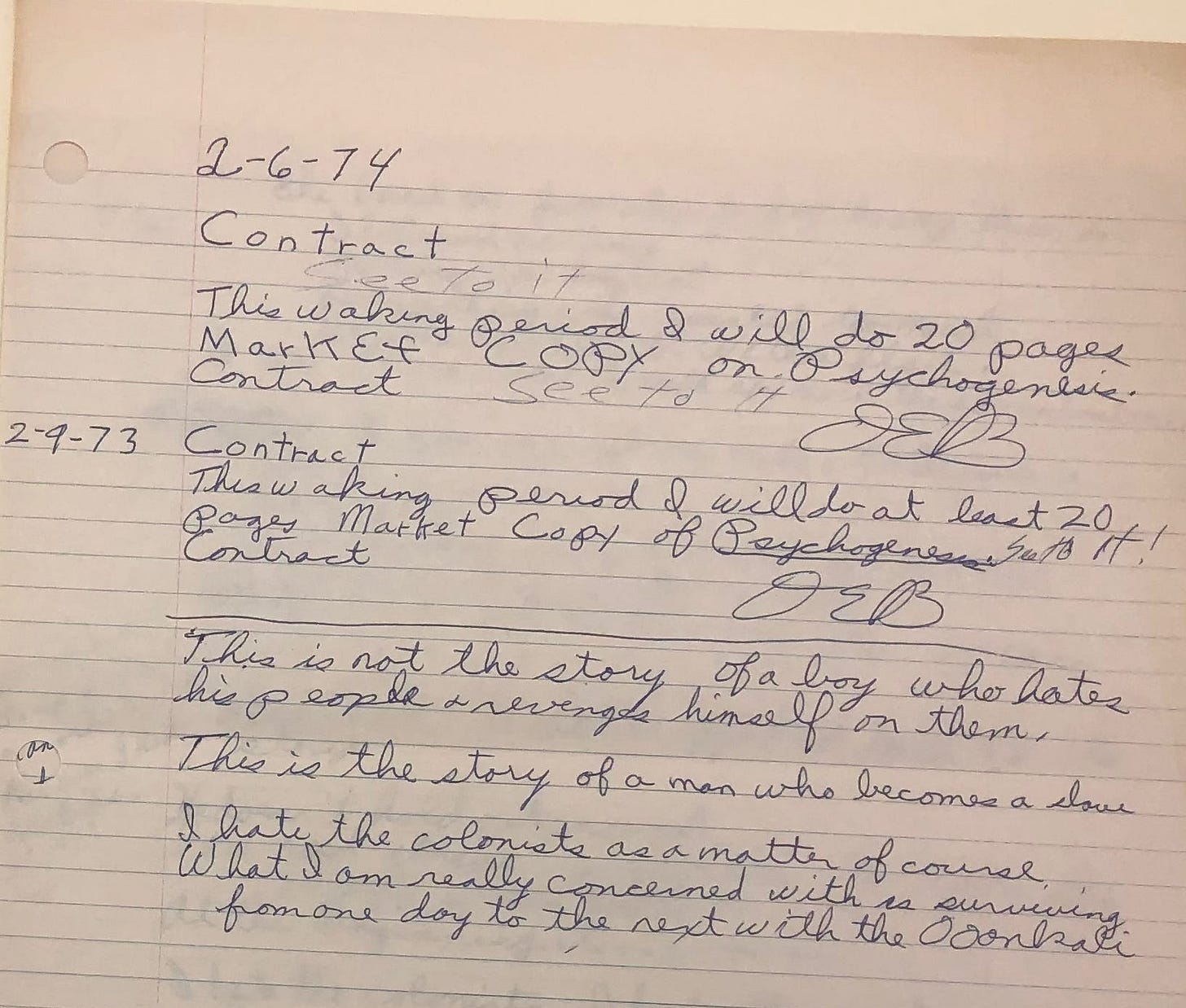

None of her essentials—motivation, persistence, determination, self-discipline, imagination, creativity, excellence, specific goals, specialized knowledge, adaptability, responsibility, cooperation, self-reliance, mental rehearsal, time management, concentration, and sustained attention—is linked to anyone else’s opinions about her or her work. They were qualities she strove to cultivate within herself, but that didn’t mean she treated them with any less respect or seriousness. She would even write and sign contracts with herself to keep her accountable.

As writers, many of us don’t get much external validation for what we’re doing—especially as we’re starting out. But that doesn’t make what we’re doing any less important. I go back and look at Butler’s notes whenever I need a reminder that internal structure, value, and accountability is more important in a creative life than the external. And at the same time, it’s important to be honest about the external things you want to achieve with your writing, whether that’s financial autonomy, fame, or making a bestseller list.

Maybe my favorite of all of Butler’s notes is this one:

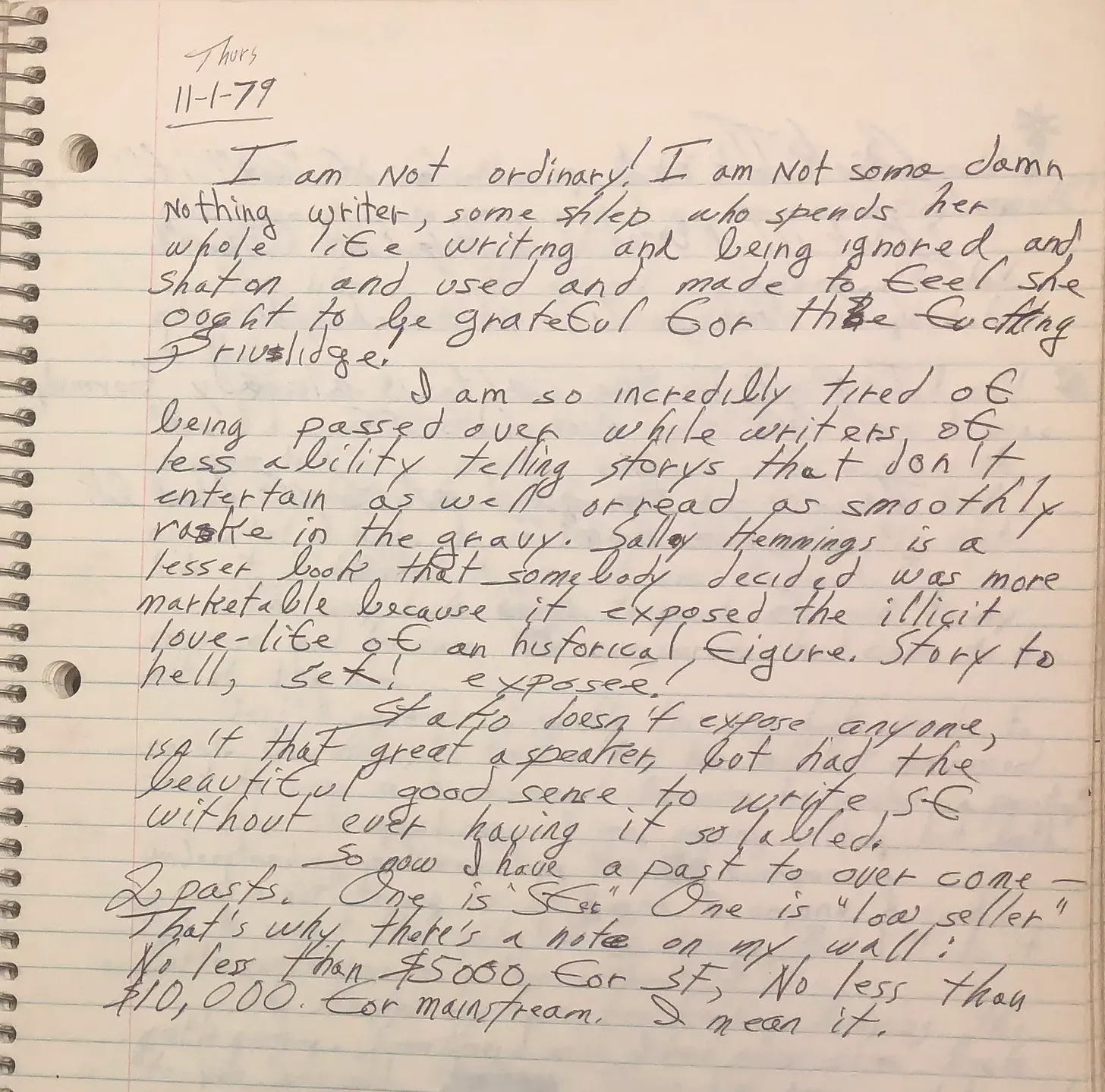

She writes, “I am NOT ordinary! I am not some damn nothing writer, some shlep who spends her whole life writing and being ignored and shat on and used and made to feel she ought to be grateful for the fucking privilege.”

Put that on your mirror, eh?

She complains about being “passed over” in favor of “writers of less ability telling storys that don’t entertain as well or read as smoothly.” I absolutely adore the pettiness, and her confidence. The note ends with a reminder about what she’ll accept:

“No less than $5,000 for [science fiction], no less than $10,000 for mainstream. I mean it.”

A petty woman who knows her worth and won’t settle for less? Now that’s sexy.

I might start signing contracts with myself, someone needs to be accountable

Oh she didn’t play!!